My Value Investing Conceptual Framework in the Tradition of Graham, Buffett and Munger.

This piece contains an overview of the principles that comprise my investment philosophy.

Introduction

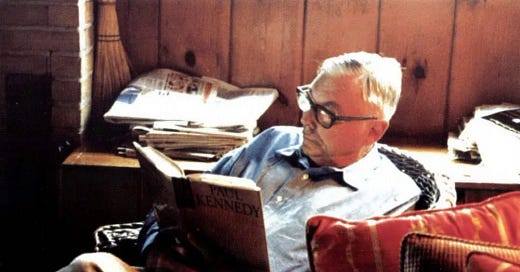

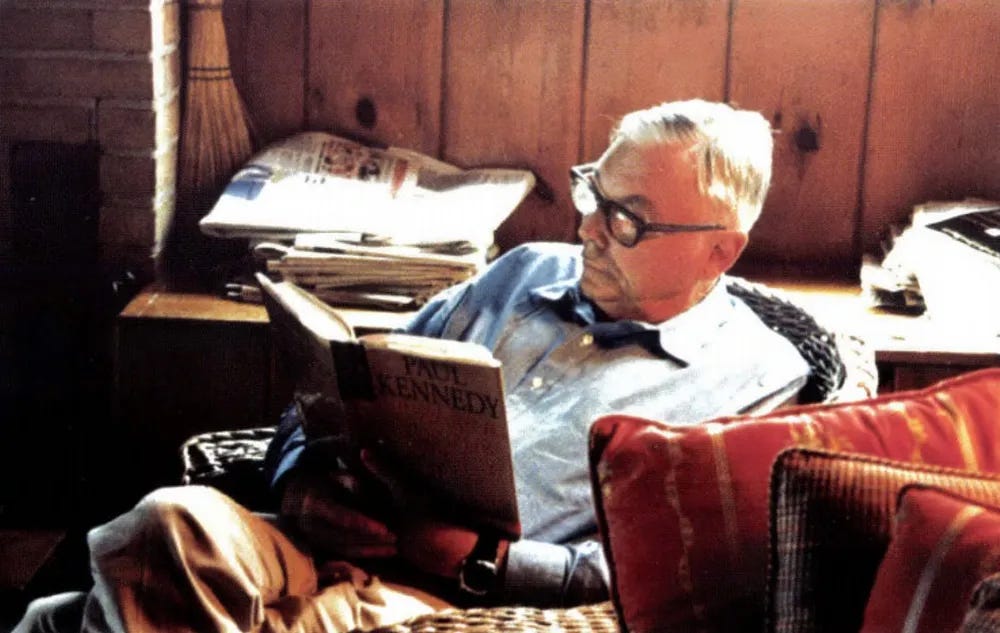

The purpose of this piece is to share with my readers the principles that compromise my personal investment philosophy. These principles are not original ideas, but rather are a collection of the best ideas that others have already figured out. As Sir Isaac Newton once said, “if I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants”. That is to say, everything that I know about investing has come from people much smarter than me who came before me. For me, those giants were Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett, and Charlie Munger.

Some readers may think to themselves that the ideas presented here are overly simplistic or nothing new. I believe those qualities are exactly what indicate the value of these ideas; they’re simple, timeless, and make logical sense. After all, simplicity is the essence of sophistication, and complexity is usually designed to bewilder and mask a lack of true understanding. To paraphrase the Declaration of Independence, I hold these investment principles to be self-evident.

Having emphasised their importance and value, my purpose in sharing them, ironically, is to destroy them if I can. Charlie Munger once said that “rapid destruction of your own ideas when the time is right is one of the most valuable qualities you can acquire”. Notwithstanding that I believe these principles to be of great value, my mind is open to being convinced otherwise. So, here’s hoping that some of my readers can persuade me to abandon, or perhaps update, my ideas.

With that litany of quotes out of the way, I present to you my investment philosophy, which is expressed from the perspective of a general partner writing to prospective limited partners in an investment partnership. I hope you enjoy reading it and that it can perhaps spark some lively debate.

Divergent Capital Investment Principles

The Partnership’s investments will be made in accordance with the following key investment principles:

The Interests of all Partners are Aligned.

The Partnership recognises and incorporates the power of incentives into its operations by aligning the interests of the General Partner with those of the Limited Partners. This is achieved by requiring that the General Partner have his own money invested in the Partnership at all times. This means that the General Partner has a strong incentive to minimise the risks faced by the partners (i.e., the risk of permanent loss of capital and the risk of underperforming the Benchmark) and to maximise the total returns earned by the partners because he is subject to the same financial outcomes as the Limited Partners, save for payment of the General Partner’s Performance Fee which the Limited Partners do not receive.

We View Stocks as Businesses.

In both a literal and legal sense, a ‘stock’ or ‘share’ is a partial ownership interest in a business. Therefore, the purchase of a stock is essentially the purchase of a business, and the task of the General Partner is to assess and value businesses, not to speculate on the price movements of stocks.

An Inactive Style of Investing is Optimal.

Every time a stock/share is bought or sold, brokerage fees are payable on the sale and purchase and capital gains taxes are payable on any realised gains. Incurring such costs frequently over time can significantly reduce investment returns. Therefore, an inactive style of investment is optimal because it preserves total returns by avoiding unnecessary costs.

There is a Difference Between Price and Value.

There is a fundamental difference between price and value. Price is what you pay, value is what you get. The price of a business (i.e., the stock price) is not necessarily the same as the business’s underlying value. The true value of a business is its Intrinsic Value.

The Market Assists but does not Instruct.

The stock market exists to assist investors, not to instruct them. This is because daily stock prices represent opportunities for investors to either buy or sell at the market price depending on whether the price offered is attractive relative to the investor’s evaluation of the business’s underlying value. Rising prices are never an instruction to buy and falling prices are never an instruction to sell, or vice versa.

In the Short-Term, the Market is a Voting Machine. In the Long-Term, the Market is a Weighing Machine.

In the short-run, stock prices are determined by the consensus of investor sentiment in the market. However, in the long-run, stock prices are ultimately determined by the business’s earnings, the price/earnings ratio (that is, the price paid for each dollar of the business’s earnings which reflects the market’s sentiment about the growth rate of earnings), and the business’s number of shares outstanding. Increases in earnings, expansion of the PE ratio, and a reduction in the number of shares outstanding result in increased business values over time.

The Value of a Business is its Intrinsic Value.

The value of a business, and the value of any economic asset (e.g., an apartment, a farm, etcetera) is equal to the present value of the asset’s future net cash flows, discounted at the prevailing or anticipated long-term interest rate. In other words, a business is worth the sums of money that it can or will pay to you over time, discounted at the prevailing or anticipated long-term interest rate. This is known as the asset’s Intrinsic Value. Intrinsic Value can be conceptualised by posing the following question: what sum of money would I need to invest today at the current or anticipated long-term interest rates to reproduce the cash flows which I anticipate that the business or asset in question will earn and be able to pay to me over its lifetime? That sum is the Intrinsic Value of the asset.

Business Valuation is an Art of Estimation and is not Capable of Precise Calculation.

The valuation of a business is an imprecise art for two reasons. Firstly, because a business’s value is determined by its future earnings. Secondly, because a business’s future earnings will inevitably fluctuate from year to year. This makes precise calculation of a business’s value impossible. Business valuation is therefore an art of estimation rather than a science of precise calculation. However, precise calculation of a business’s value is not necessary so long as the investor can estimate the business’s value and pay a price that is lower than that estimated value.

Investment Returns are Ultimately Determined by Business Results.

In the long-term, an investor’s return on his investment in a business (and hence, his investment in a stock) will be determined by the rate of return return earned on the capital invested in the business. In other words, the fate of the investor is tied to the fate of the businesses in which he invests. For this reason, we primarily seek to invest in high quality businesses.

We Invest in Good Businesses.

Because good businesses often make the best investments, we seek to invest in good businesses. A good business, like a good investment, is one that earns a high rate of return on invested capital. Furthermore, businesses are a means of compounding capital. For this reason, the duration of the returns on capital earned by a business is also a critical component of investment returns because the key ingredients for optimal compounding are high rates of return and a long duration.

Businesses that earn high rates of return on invested capital are those that have some combination of the following characteristics:

A “competitive advantage” that makes the business resistant to effective competition which would otherwise decrease economic returns, or which allows it to earn high rates of return in spite of limited competition. The durability of a business’s competitive advantage determines the duration of its returns.

High rates of return on invested capital, as measured by free cash flow (net income plus non-cash items less maintenance capital expenditures) relative to the capital employed in the business (net working capital, fixed assets and long-term debt).

Able and honest management, preferably with the ability to allocate capital effectively and who have an ownership stake in the business.

Opportunities for the business to reinvest some or all of the capital it earns at the same high rates of return, which produces a compounding effect.

A stable and consistent operating history.

Stable and predictable economic characteristics in industries that are resistant to technological change.

The ability to raise prices due to either:

The price of the company’s products representing a small proportion of the consumer’s budget (e.g., Coca Cola, Hershey’s chocolates);

Consumers associating the company’s products and their high prices with status and exclusivity (e.g., LVMH, Ferrari); or

The company’s product serving an important function with a lack of close substitutes; and

A business which derives its earnings predominantly or solely in cash.

We Avoid Purchasing Bad Businesses.

Conversely, we avoid purchasing bad businesses. A bad business is one that either earns a low return on invested capital or whose duration of returns is short-lived. Either of these characteristics or a combination of both leads to suboptimal compounding of capital. Furthermore, bad businesses pose a greater risk of permanent loss of capital via bankruptcy. For these reasons, the Partnership’s capital will never be invested in bad businesses.

Bad businesses often have some combination of the following characteristics:

No discernible competitive advantage, meaning that there is nothing to prevent other companies from beginning to compete with the business in question and thereby diminishing or completely eroding the business’s returns on capital;

Commodity product businesses: businesses which deal in products that are identical to those of its competitors. For example, mining companies, oil and gas exploration companies.

Businesses that dilute current shareholders’ ownership of the business by issuing more shares.

Businesses with returns on invested capital of less than long-term interest rates.

We do not Follow Investment Mandates.

Many investment firms limit themselves through ‘mandates’ which require that they invest in particular types of businesses, delineated by criteria such as market capitalisation or geography. We do not limit ourselves by such criteria and we seek out high quality businesses regardless of geography or market capitalisation size, although we do take into account the potential effects of these factors on the safety of principal provided by the investment.

We make Decisions within our Circle of Competence.

Risk is created by not knowing what you’re doing. This is because, when you don’t understand what you’re doing, you can’t make intelligent decisions. In order to minimise risk, we make decisions within our circle of competence. This simply means sticking to what we know and can understand, which involves exercising intellectual honesty by admitting when a subject matter is beyond your understanding or comprehension. An investor operates within his circle of competence by only investing in those businesses which he can understand. Understanding a business means understanding its economic characteristics, its competitive advantage, and the durability of the competitive advantage, both now and in the future. In investing, operating within your circle of competence is important because an investor cannot intelligently monitor ownership of a business which he does not understand.

We Concentrate Rather than Diversify our Holdings.

The Partnership will typically (but not necessarily) own between 1 and 10 businesses and will therefore be concentrated rather than diversified.

There are five important justifications for this policy of concentration:

Firstly, concentrating the Partnership’s investments promotes a higher thresholding of understanding of the businesses that the Partnership owns.

Secondly, there are only so many businesses which the General Partner is capable of understanding and this naturally limits the Partnership’s number of potential investments.

Thirdly, there is a limited number of high-quality businesses that are worth owning within the investable universe of businesses, which naturally limits the Partnership’s number of potential investments.

Fourthly, concentrated investments have a greater effect on the Partnership’s overall performance. For example, if an investment which represents 1% of the Partnership’s total funds triples in value, this is equal to a 3% return on the Partnership’s total funds. By contrast, if an investment which represents 20% of the Partnership’s total funds earns a return of 50%, this represents a 10% return on the Partnership’s total funds.

Fifthly, we make investment decisions based on opportunity cost. This means that we measure the attractiveness of a prospective investment against the attractiveness of what we already own and can buy more of and forego a prospective investment if it is less attractive than buying more of what we already own. In our view, it is illogical to invest money in your third best idea when your best idea is still available for purchase. Making investment decisions based on opportunity cost naturally leads to concentration because it means pursue your best idea at any given time to the exclusion of all others.

We Exercise Patience and Wait for a “Fat Pitch”.

Although we relentlessly seek out opportunities due to our love of the hunt, we also exercise patience by withholding action until we find an opportunity that is both understandable and highly attractive. This is what’s called the “fat pitch”: an opportunity we can swing hard at and hopefully hit a home run with. This then ties in with our investment principle concerning concentration. When we find such an opportunity, we swing hard by taking a sizeable position. In other words, we bet heavily when the odds are in our favour. Otherwise, when there’s nothing to do, in the sense that there are no attractive opportunities available, we do nothing.

The Best Holding Period is Forever.

As previously mentioned, businesses are a means of compounding capital and the key ingredients for optimal compounding are high rates of return and a long duration. When we have the opportunity to purchase a high-quality business at a reasonable price, our preferred holding period is forever, so long as the business continues to exhibit the characteristics of a high-quality business, and the business’s competitive advantage is not eroded. A long holding period allows us to maximally reap the rewards of compounding. Additionally, a long holding period avoids unnecessary brokerage fees and capital gains taxes which are incurred by selling and which reduce investment returns.

There are Only Three Reasons to Sell a Business.

Notwithstanding our preferred holding period of forever, there are three circumstances in which we will contemplate selling a business:

When there was a factual mistake in the initial analysis and one of the reasons for the initial purchase of the business proves to be incorrect;

When there is an adverse change in the facts, such as the competitive position of the business deteriorating; or

When the Partnership has access to limited capital and believes that it has found a potential investment that is more attractive than one of its current holdings.

Risk Means the Possibility of Harm or Loss Occurring.

Risk means the possibility of loss or harm occurring. In investing, the primary risk is the risk of permanent loss of capital. Capital can be permanently lost in three possible ways. Firstly, by panic selling at low prices, which thereby turns “paper losses” into actual losses. Secondly, by purchasing subpar businesses which later become bankrupt. Thirdly, by overpaying for high quality businesses, whose valuation never reaches the price paid in advance for the business.

Additionally, partners are at risk of suffering an implicit loss (i.e., an opportunity cost). This loss arises if the General Partner fails to outperform the Benchmark over a given 5-year period or over the life of the Partnership. The cost is equal to the difference between what the partners could have earned had they invested in the Benchmark and what they actually earned by investing in the Partnership (i.e., what they missed out on).

Volatility and Risk are Not the Same.

In investing, volatility means the fluctuation of market prices. Consistent with our other investment principles, we do not view volatility as being equivalent to risk. This is because fluctuating market prices provide an investor with the opportunity to either buy or sell advantageously if the price offered is attractive relative to the appraised intrinsic value of the business. In other words, volatility is not equivalent to risk because, firstly, market prices are distinct from business values; and secondly, because the market serves but never instructs the investor.

The Risk of Permanent Loss of Capital is Mitigated by the Margin of Safety Concept.

Investment risk, that is, the risk of permanent loss of capital, is primarily mitigated by the Margin of Safety principle. The Margin of Safety principle stipulates that there must always be a favourable difference between the price paid for a business and its estimated intrinsic value. The purpose of the margin of safety is to provide room for error in the event that the investor’s appraisal of business value proves to be incorrect. Room for error in the purchase of businesses is required because business valuation is an art of estimation and is not capable of precise calculation. If an investor pays a price for a business that is far less than its estimated intrinsic value, then room for error is provided by that difference in the event that the estimated intrinsic value proves to be closer to the price paid than originally thought. Furthermore, the greater the difference between the price paid for a business and its intrinsic value, the greater the reward when the market revalues the business upwards to its intrinsic value. In other words, the Margin of Safety principle provides both reduced risk and increased reward.

The Risk of Permanent Loss of Capital is also Mitigated by Weighting Investments by Conviction.

The Partnership’s individual investments are weighted by conviction. This means that the Partnership’s most attractive ideas receive the most capital, and the Partnership’s least attractive ideas receive the least capital. In essence, weighting investments by conviction involves making a judgment about the expected value of the investment, which takes into account both the probability of gain and the amount of possible gain, less the probability of loss and the amount of possible loss.

Weighting investments by conviction mitigates the risk of permanent loss of capital by devoting the greatest amount of capital to those ideas which are appraised to be the safest and most attractive, and the least amount of capital to those ideas that are appraised to be the least safe and attractive, relative to the other available opportunities. This means that the potential downside is limited.

Risk and Reward are Not Necessarily Correlated.

One advantageous aspect of value investing is that the larger the discount from intrinsic value, the greater the margin of safety and the potential return when the stock price converges on the intrinsic value. Contrary to the view that increased returns can only be achieved by taking greater levels of risk, value investing is based upon the notion that increased returns are associated with a greater margin of safety, i.e. lower risk.

We Make Investment Decisions Based on Opportunity Cost.

In investing, the Opportunity Cost of an investment is the cost of foregoing your next most attractive idea. Opportunity Cost serves as the yardstick by which the attractiveness of any potential investment is measured. We assess the attractiveness of a prospective investment against the attractiveness of what we already own. We only purchase a new business when we believe that the new purchase is more attractive than further purchases of what we already own. The reason for this is that it would be illogical to make a new investment if it were possible to purchase more of what we already own if we believe this to be the more attractive option.

We Ignore Macroeconomic Factors.

The General Partner’s primary task is the analysis, valuation, and purchase of high-quality businesses. In undertaking that task, we focus on information that is both knowable and important. We believe that macroeconomic factors, such as future interest rates, the future rate of inflation, future commodity prices, etcetera, are unpredictable and unknowable. Therefore, we disregard future macroeconomic factors in making our investment decisions.